This is a follow up from part 1 (you’re shocked, I can tell). Read that for some more context.

The fact that the research has lasted over nine years (2016-2025) has been tough, but its also had some benefits. being honest it makes me cringe thinking about how many commercial design research projects (and even whole services or organisations) I’ve worked on in that time. But, that time has also allowed for the reflections gathered from doing and observing service design in different contexts, as well as other people developing their thinking and writing as well. Read on for more details about each of these…

Differences between commercial and academic design research

It has been petty tough to look back on the number of very similar (and often much larger) commercial projects that I have been involved in over the years that the overall research project was completed. Given I explicitly took a ‘design research’ approach to the research (small sample sizes, iterative analysis etc), It’s even easier to draw comparisons between commercial projects that are measured in weeks, and this work that has ended up taking years.

This is in part due to the ‘rigour’ needed for doctoral study, but it primarily comes down to completing study part time, alongside three different design leadership roles, and raising a young family (I didn’t even have kids when i started this).

A quick reflection on rigour. I frequently questioned whether the work carried out was sufficiently ‘rigourous’ as I imagine a lot of people do when using qualitative research methods. Conversations with my supervisors supported my proposed approach (They get design research as a thing), but also focusing on my stated intent to take a ‘pragmatist’ approach that recognised the inherent constraints of doing part time research, based on commercial design practice. I especially found the following definition of rigour helpful to my work:

“Rigour consists only of being able to show your peers that the material you have gathered is reasonable as a response to the purposes of the investigation, and of sufficient quality and volume to make a contribution to your particular scholarly audience.” (Matthews and Brereton 2014)

Given that my peers and the intended audience in this context are service design practitioners, who often have limited exposure to academic literature, it made sense to use their expectations to inform my research approach.

Development of new literature

Because of the time that I took completing the work, I was forced to revisit literature (as any good researcher should do regularly) to check what new things had been published on relevant topics. I had expected there would be quite a lot published from authors specialising in prototyping, as well as work from new authors. Honestly, it was surprising how little had happened in this space over nine years.

There was some new work published that explores similar themes to my own (Unveiling the complex and multiple faces of fidelity & Innovation by service prototyping ) as well as others publishing reflections on mixed fidelity. Its obviously a topic of interest to designers, but hasn’t really been developed more for service design. I considered Abdel Razek’s work in much more detail within the final project report – but I was ultimately struck that I wasn’t seeing it being discussed or adopted by anyone practicing service design as far as I could see. That reinforced my desire to focus on communicating my work effectively to people in design roles, rather than other academics.

Evolving work practices

Design practice has naturally changed over nine years, as you’d expect, with change accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The resultant shift to hybrid working models has fundamentally altered how design teams collaborate and prototype.

Practically this meant all of the interviews research for the final project (2021-2022) were done remotely. Even when this was no longer essential, it had become the established norm with people from other orgs especially. I think its unlikely this had any significant impact on the research itself and again, the pragmatist approach is one that adapts to context, rather than attempts to control it. Adapting to remote ways of working has been part of this.

Within workplaces, many teams moved from being fully in-person to being entirely remote, and then back to some form of ‘hybrid working’ where they are physically together for part of the working week. This has driven the adoption of digital whiteboards (Miro, Mural etc) and other tools to support remote working. I’ve personally experienced this, and it was also mentioned within the interviews carried out for the project. When I started this research project I worked 5 days a week in a design studio, moving to primarily working remotely with limited visits to offices for workshops/meetings as necessary by the end of completing the research.

In my experience physical design studio spaces often provide designers with the resources and space to create physical prototypes, encouraging designers to physically sketch, build and test ideas together. Remote working tools can replicate some of this, but it has had an impact on some of the prototyping methods that are associated with service design. Common methods that have been identified through this work such desktop walkthroughs, role plays and service walkthroughs (see Service Design tools & Service Design Doing) are in person, physical activities that are challenging to replicate digitally fully.

Given that many design teams are now primarily remote (which has opened a whole host of opportunities), there’s probably a bigger piece of work to explore the impact on prototyping approaches for these teams in more detail. The proposed mixed fidelity framework I ended up with doesn’t explicitly refer to teams working remotely – but it is likely that if that is the dominant way of working that prototypes are being created in, it will have a significant impact on how prototypes are discussed and created.

Designer’s limited exploration of fidelity

Working with and speaking to people working in different environments has given me a deeper resource of stories about prototypes but has also revealed how few have deeply thought about the role of fidelity in prototyping. I’ve seen designers struggle to articulate the reasons for their prototyping approaches or connect their practice to broader design theory. For me this increased my confidence that the work I was doing was worth doing, given there appeared to be a need. But it also highlighted the need for the work to be communicated effectively as possible, rather hidden behind academic paywalls or language.

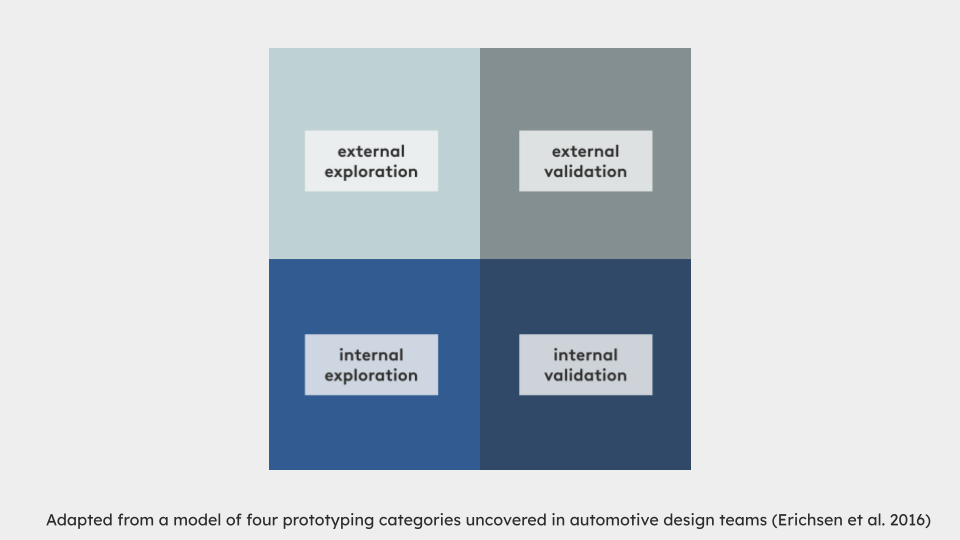

One way I noticed this was that I found myself sharing some of the content of my literature review work with participants and other colleagues to support broader design conversations. Examples I’ve used a lot are the 2×2 matrix of approaches to prototyping based on observations in the automotive industry:

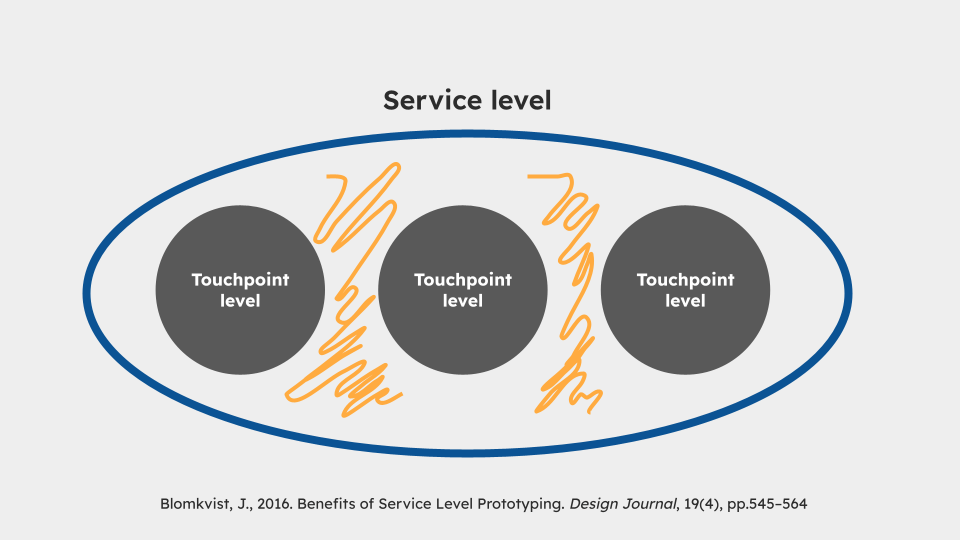

And the concept of ‘Service Level Prototyping’ from Johan Blomkvist.

This made me reflect on how true that’s been of myself as well over the time of this research. Creating the final framework isn’t necessarily where I’ve got most value. Lots of that value has come from the underpinning research that has shaped how I talk about prototyping more broadly. The literature review work in particular, and trying to maintain a current view of literature, and critically considering professional and grey literature has made a big different to my own perspective on service design prototyping.

Wider service theory

Its not just service design prototyping literature either. Concepts like value creation in service-dominant logic influence design practice, even when not explicitly acknowledged or understood by designers. This wider reading has enabled me to develop language and conceptual models that support my service design practice, from a wider pool rather than simply popular design authors or publishers.

Value creation as explored within S-D Logic isn’t explicitly reflected in the final framework or the community of practice sessions but along with similar concepts has supported me to engage with other professions within organisations such as marketing – given that much of this was developed as part of service marketing theory. Understanding more context within service research development has also allowed me to recognise where people I’m working with, or speaking to hold a fundamentally alternative view on how to create value (embedding value vs co-creating value) and the resulting impacts this has on how they carry out design research and innovation work.

There is a broader challenge here around how we enable designers – or anyone else involved in designing and delivering services to read & reflect on a wider range of literature. So much of it is hard to practically access, or uses inaccessible language. It makes me wonder what the opportunity is here to improve the transfer between academia and practice. Not necessarily for the new cutting-edge ideas, but for some broader professional context and grounding to help people understand different mental models rather than simply those that are dominant in their own field or organisation.

Leave a comment